In the study of law, there is the concept of the loophole. Lawyers may spend a long time studying legal loopholes and finding ways to exploit them. Loopholes also exist in the laws of nature. Much of engineering and design work consists of discovering new ways to exploit these loopholes. In permaculture design, one of the more important loopholes that we exploit is the edge effect.

The edge effect is the phenomenon of the collection of surplus on edges. In nature, not only does surplus collect on edges, but edges are the only places where surplus occurs.

But what is edge, in essence? Where media join, there are edges. Those edges can be more or less complex. An edge is the interface. It is that steel-strong film, the surface between the water and the air; it’s that zone around a soil particle to which water bonds with such fantastic force. It’s the shoreline between land and water. It is the interface between forest and grassland. It is the scrub, which you can differentiate from grassland. It is the area between the frost and non-frost level on a hillside. It is the border of the desert. The edge effect can be seen everywhere. The most species of birds can be found not in the forest, nor in the field, but in the bushes at the forest edge. Both the forest birds and the plains birds spend some time in the bushes, and there are specialized edge species that specifically live in the bushes at the edge of the forest. This is a pattern that you can see throughout nature. Every edge between ecosystems has an edge ecosystem of its own, and that is precisely where the greatest biodiversity and the greatest fertility is. You can even see the edge effect in the way trash piles up against a fence on a windy day.

In practice, how do we use the edge effect in design? Well, it depends on what kind of edge it is. There are beneficial and not so beneficial edges. When two dissimilar systems meet each other one or both of them may respond with a decrease in yield But, in general we see that the edge is very rich, because in it there are species of one and the other system, plus species that are unique to the edge itself. It would be quite difficult to grow tomatoes on the edge of a pine forest. Nevertheless, you can grow a good harvet of blueberries there. There are no doubts about this. If it’s a beneficial edge, like the edge between a pasture and a forest garden, we extend it, within practicality, in order to maximize the beneficial edge effect. This is why, when we install swales, we don’t flatten the land first, so that the swales can be straight lines. We build them on contour because when they curve, there is more length of swale in proportion to the area, which means more volume of water capture. Flattening the land would not only cost more, but it would decrease the amount of water we could capture at a time. Detrimental edges are something we try to entirely eliminate, by putting buffering elements between other elements that might harm each other, but when that is impractical, we minimize them. For instance, if you have a zone 1 mulched garden, you need it to be free of quack grass, which is about the only weed that mulched gardens are vulnerable to. But your yard is full of it. So you use some pigs to completely eliminate all plants in the area where you plan to have your garden. But if you don’t maintain the edge of your garden, quack grass can invade it from outside, spreading to your garden by rhizomes. So to minimize maintenance, you make the garden as close to circular as practical, since a circle has less edge than any other shape, and you create a rhizome barrier with comfrey. Then you add a border of onions within the border of comfrey, to deter rodents. Then you already have some ideas for which plants to put near the edge, because there are certain You design the edge first, and by the time the edge is worked out, you already know what to do in the area.

It’s unfortunate that when we think in terms of yield over area, we often discount the advantages that we can gain by incorporating beneficial edges into the production space. When you are digging a pond for aquaculture, one thing you can do is make a really complicated edge between the land and the water, creating a lot of shallow areas that are ideal for frogs to lay eggs in. Ponds with that feature included have been known to appear black just from the sheer numbers of tadpoles swimming in them. Tadpoles are perfectly good fish food, as are insect larvae, which also need a shallow area to hatch. These shallow areas are also ideal for growing wild rice, which is a very valuable crop, as well as a high-yielding duck forage.

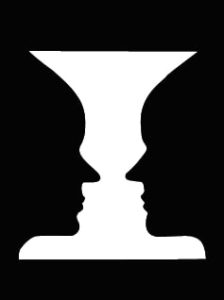

Edge is about more than just another technique. It’s a whole new way to think about the way you design. The relationship between the edge and the area is quite important. It is the edge that defines the area. A classic example of this is the optical illusion of the two faces and the vase.

The edges of the vase define the faces, and the edges of the faces define the vase. It is the edge that defines the area. Hence the shape and positioning of the area and the elements around it is at least as important as the specific techniques used in the area.

It is at the edge of a fish pond that you plant your white mulberry tree. The berries are fish food, as are the silkworms that eat the mulberry leaves. You put a hedge of yellow acacia at the edge of a garden, because it fertilizes the garden, gives a yield of beans, provides mulch for the garden, and is beneficial to a forest garden or a pasture on the other side of it. If you had a garden without a hedge, you couldn’t put a pasture right next to it. You have to design the edge to be a beneficial one.

The subject of edge and the edge effect is very expansive, and it leads to an even more interesting discussion about the role of pattern in design, but I will leave that for a later issue.

Image sources / Источники изображений

Leave a Reply